Terror with Glaze

The 2016 US Presidential Election has seen its share of controversies and hot-button topics, from the leaked Clinton e-mails to Donald Trump’s statements on Muslims. All have weighed in on the horrible attacks on Paris and Brussels, the threat of ISIS, and even Apple’s fight with the FBI over an encrypted iPhone.

As someone in the technology space, the encryption fight has been simultaneously interesting and concerning to me, as any precedent set could cause serious problems for the privacy and security of all those on the Internet.

The concern by the authorities is that technology-based encryption (which can be impossible to intercept and crack) makes it extraordinarily difficult to stop the next impending attack. Banning encryption, on the other hand, would mean making the average phone and Internet communication less secure, opening the door to other types of threats.

This is an important topic, but what few in the media talk about is that terrorists have been using an alternative method for years before encryption was available to the masses. They don’t talk about it because it hits maybe too close to home.

They don’t talk about the dangers of your local donut shop.

Passing coded messages

Passing a message between conspirators is nothing new. Just as little Tommy might write a coded note in class to Sally so the teacher couldn’t find out, terrorists, crime syndicates, and spy agencies have been using all manner of coded messages for thousands of years to keep their communication secure. Such messages could be passed right in front of others’ noses, and none would be the wiser.

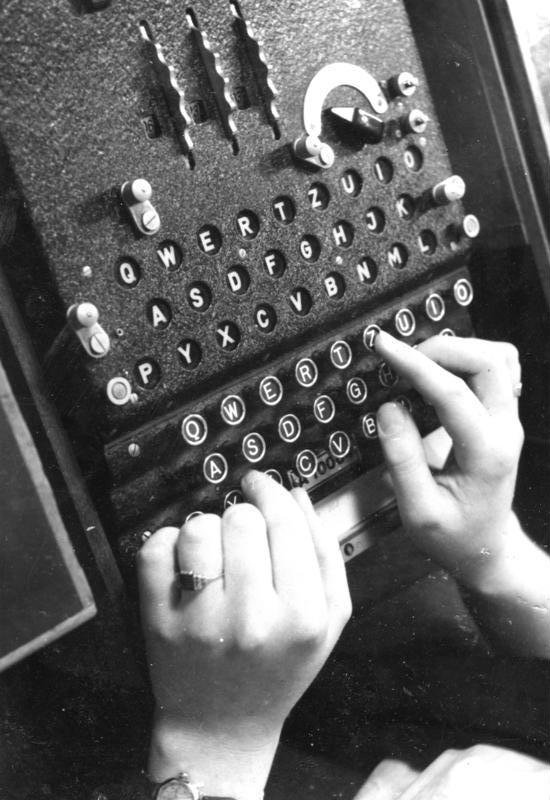

These have been used all throughout history. The German Enigma Code is perhaps one of the most famous examples.

Such messages often entail combinations of letters, numbers, symbols, or may contain specialized words (“The monkey flaps in the twilight,” for instance) that appear as gibberish to most, but have very specific meaning to others. The more combinations of letters, numbers, symbols, or words, the more information you can communicate, and the less likely it is that someone will crack it.

That said, many of these have been cracked or intercepted over time, causing such organizations to become even more creative with how they communicate.

The Donut Code

Donuts have a long history, and its origins are in dispute, but it’s clear that donut shops have been operating for quite some time now. They’re a staple in American culture, and you don’t have to drive too far to find one. Donuts also come in all shapes, sizes, and with all sorts of glazes and toppings, and it’s considered normal to order a dozen or so at once.

In other words, it’s a perfect delivery tool for discrete communication.

When one walks into a donut shop, they’re presented with rows upon rows of dozens of styles of donuts, from the Maple Bar to the Chocolate Old Fashioned to the infamous Rainbow Sprinkle.

While most will simply order their donuts and go, those with something to hide can use these as a tool, a message delivery vehicle, simply by ordering just the right donuts in the right order to communicate information.

Let’s try an example

“I’ll have a dozen donuts: 2 maple bars, 1 chocolate bar, 2 rainbow sprinkles, 3 chocolate old fashioned, 1 glazed jelly, and 2 apple fritters. How many do I have? … Okay, 1 more maple bar.”

If top code breakers were sitting in the room, they may mistake that for a typical donut order. Exactly as intended. How could you even tell?

Well, that depends on the group and the code, but here’s a hypothetical example.

The first and last items may represent the message type and a confirmation of the coded message. By starting with “I’ll have a dozen donuts: 2 maple bars,” the message may communicate “I have a message to communicate about <thing>”. Both the initial donut type and number may be used to set up the formulation for the rest of the message.

Finishing with “How many do I have? … Okay, 1 more maple bar.” may be a confirmation that, yes, this is an encoded message, and the type of message was correct, and that the information is considered sent and delivered.

So the above may easily translate to:

I have a message to communicate about the birthday party on Tuesday.

We will order a bounce house and 2 clowns. It will take place at 3PM. There will be cake. Please bring two presents each.

To confirm, this is Tuesday.

Except way more nefarious.

Sooo many combinations

The other donut types, the numbers, and the ordering of donuts may all present specific information for the receiver, communicating people, schedules, events, merchandise, finances, or anything else. Simply change the number, the type of donut, or the order, and it may communicate an entirely different message.

If a donut shop offers just 20 different types of donuts, and a message is comprised of 12 donuts in a specific order, then we’re talking more combinations than you could count in a lifetime! Not to mention other possibilities like ordering a coffee or asking about donuts not on the menu, which could have significance as well.

Basically, there’s a lot of possible ways to encode a message.

The recipient of the message may be behind the register, or may simply be enjoying his coffee at a nearby table. How would one even know? They wouldn’t, that’s how.

Should we be afraid of donut shops?

It’s all too easy to be afraid these days, with the news heavily focused on terrorism and school shootings, with the Internet turning every local story global.

Statistically, it’s unlikely that you will die due to a terrorist attack or another tragic event, particularly one related to donuts. The odds are in your favor.

As for the donut shop, just because a coded message may be delivered while you’re munching on a bear claw doesn’t mean that you’re in danger. The donut shop would be an asset, not a target. It may even be the safest place you can be.

So sit down, order a dozen donuts, maybe a cup of coffee, and enjoy your day. And please, leave the donut crackin’ to the authorities. They’re professionals.

(I am available to write for The Onion or Fox News.)